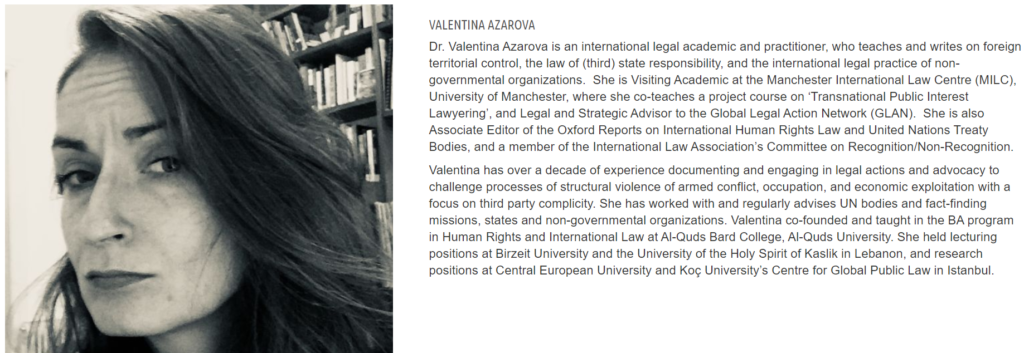

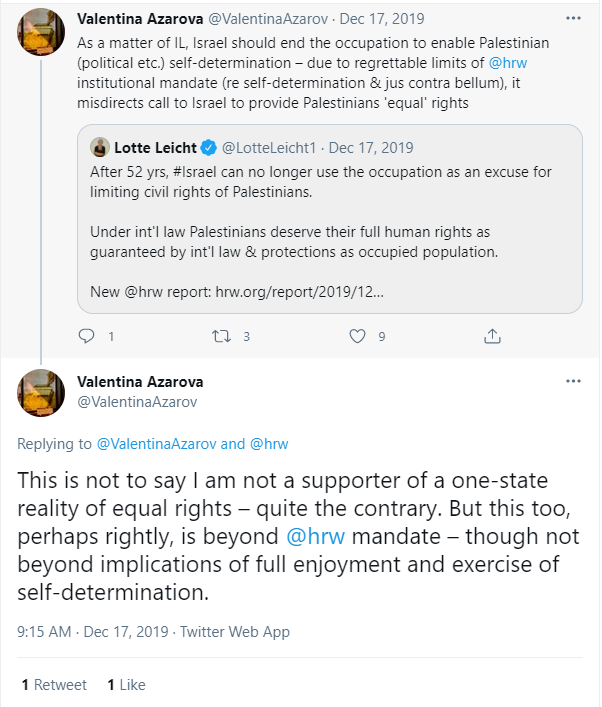

Back in November 2020, we covered the case of Valentina Azarova, a Germany-based “human rights scholar” who was denied the directorship of the University of Toronto School of Law International Human Rights Program (IHRP). Outraged, her supporters complained that a Jewish alumnus and donor—a sitting Tax Court judge ill-disposed to Azarova’s work on “Israel’s occupation of Palestine”—prevented her hire via behind-the-scenes pressure. Now, an independent investigation has disproven this claim, but Azarova’s advocates are sticking to—and relentlessly spreading—their original, false narrative.

Contents

Background: The Job Offer That Wasn’t

As our November 8th, 2020 post, Claims That U. Toronto Succumbed To Zionists In Denying Human Rights Position To Valentina Azarova Fall Flat, explained:

The initial narrative that emerged in this case is one in which a Jewish Tax Court judge [David Spiro], reportedly furious about Valentina Azarova’s “criticism” of “Israeli human rights abuses” against Palestinians, may have used his status as a[n alumnus and] “major donor” to pressure the university to rescind its job offer [for the post of International Human Rights Program (IHRP) director—which, Azarova claimed, had already been officially offered to her].

Shree Paradkar, The Toronto Star‘s “race and gender columnist”, first broke the story in mid-September [2020]. Since then, she has covered the controversy extensively; she’s written at least eight articles about it since September 17th.

But, as is usual in cases of controversy over academic anti-Israel demagoguery, there may be more to the story than The Star’s Paradkar (among others) would have you believe.

Indeed, as we reported in November,

[T]he university insists that it never actually extended a formal offer of employment to Azarova.

The university said while “exploratory discussions occurred with one candidate,” it backed the assertion by [UT Law dean] Edward Iacobucci in his email [to UT Law staff, addressing the controversy after the story broke] that, “No offer of employment was made because of legal constraints on cross-border hiring that meant that a candidate could not meet the Faculty’s timing needs.”

Kelly Hannah-Moffat, vice-resident of human resources and equity [at UT], reportedly stated,

We can confirm that no offer of employment was made to any candidate, and therefore, no offer was revoked. The Faculty of Law has cancelled the search. No offers were made because of technical and legal constraints pertaining to cross-border hiring at this time.

It soon emerged that among those who first complained publicly about the choice to pass on Azarova was Samer Muscati—a fellow anti-Zionist academic who previously held the position for which Azarova was rejected, and who later became an official with the historically anti-Israel NGO Human Rights Watch (HRW). As such, Muscati is presumably connected to Bill Van Esveld—himself a long-time Middle East-focused HRW official with his own history of endorsing false claims and biased reports about Israel—and who happens to be married to Azarova.

Back in November 2020, we covered the case of Valentina Azarova, a Germany-based “human rights scholar” who was denied the directorship of the University of Toronto School of Law International Human Rights Program (IHRP). Outraged, her supporters complained that a Jewish alumnus and donor—a sitting Tax Court judge ill-disposed to Azarova’s work on “Israel’s occupation of Palestine”—prevented her hire via behind-the-scenes pressure. Now, an independent investigation has disproven this claim, but Azarova’s advocates are sticking to—and relentlessly spreading—their original, false narrative.

ContentsBackground: The Job Offer That Wasn’t

As our November 8th, 2020 post, Claims That U. Toronto Succumbed To Zionists In Denying Human Rights Position To Valentina Azarova Fall Flat, explained:

The initial narrative that emerged in this case is one in which a Jewish Tax Court judge [David Spiro], reportedly furious about Valentina Azarova’s “criticism” of “Israeli human rights abuses” against Palestinians, may have used his status as a[n alumnus and] “major donor” to pressure the university to rescind its job offer [for the post of International Human Rights Program (IHRP) director—which, Azarova claimed, had already been officially offered to her].

Shree Paradkar, The Toronto Star‘s “race and gender columnist”, first broke the story in mid-September [2020]. Since then, she has covered the controversy extensively; she’s written at least eight articles about it since September 17th.

But, as is usual in cases of controversy over academic anti-Israel demagoguery, there may be more to the story than The Star’s Paradkar (among others) would have you believe.

Indeed, as we reported in November,

[T]he university insists that it never actually extended a formal offer of employment to Azarova.

The university said while “exploratory discussions occurred with one candidate,” it backed the assertion by [UT Law dean] Edward Iacobucci in his email [to UT Law staff, addressing the controversy after the story broke] that, “No offer of employment was made because of legal constraints on cross-border hiring that meant that a candidate could not meet the Faculty’s timing needs.”

Kelly Hannah-Moffat, vice-resident of human resources and equity [at UT], reportedly stated,

We can confirm that no offer of employment was made to any candidate, and therefore, no offer was revoked. The Faculty of Law has cancelled the search. No offers were made because of technical and legal constraints pertaining to cross-border hiring at this time.

It soon emerged that among those who first complained publicly about the choice to pass on Azarova was Samer Muscati—a fellow anti-Zionist academic who previously held the position for which Azarova was rejected, and who later became an official with the historically anti-Israel NGO Human Rights Watch (HRW). As such, Muscati is presumably connected to Bill Van Esveld—himself a long-time Middle East-focused HRW official with his own history of endorsing false claims and biased reports about Israel—and who happens to be married to Azarova.

These relationships could help explain why—even in view of the many obscene human rights violations around the globe on which she could have devoted her attention—HRW Canada director Farida Deif wrote and posted an impassioned defense of Azarova on HRW’s website. Deif opined that if “external pressure about the candidate’s scholarship and work on Israeli government violations of international law” influenced the university’s choice, “not only does this do serious harm to the academic freedom, integrity, and reputation of the university’s human rights program, it creates a dangerous chilling effect on other scholars’ rights to research and advocacy.” Deif also happens to be a close colleague of Azarova’s husband Bill Van Elsveld; she even acknowledged as much in her Azarova piece.

Meanwhile, the UT Law faculty selection advisory committee chairperson—apparently enthusiastic about Azarova from the start—was (now resigned) professor Audrey Macklin. Macklin, too, has a long history of anti-Israel activism and connections to the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) campaign against the Jewish state.

Yet, their concerns about “academic freedom” and “external pressure” seemed irrelevant when it came to Azarova advocates’ own connections and behavior.

Predictably, Azarova’s supporters are not mollified that an independent investigation has corroborated the university’s original claims that Azarova was never formally offered the job, and that the decision not to hire her was based on legal and immigration difficulties, rather than outside influence.

Independent Investigation: A Narrative Contradicted

On March 15, 2021 former Canadian Supreme Court justice Thomas Cromwell—who’d been hired by the university to investigate the allegations against Judge David Spiro and UT Law dean Edward Iacobucci—submitted his report on the Azarova affair. Even The Toronto Star had to admit that Justice Cromwell “concluded external influence played no role and that serious obstacles relating to immigration were behind U of T’s decision.” (Emphasis added.)

You can read the entire document here .

After Justice Cromwell’s report was publicly released, the Law Times summarized the report’s findings in an article on its website (emphasis added):

Despite accusations that Azarova’s job offer was withdrawn after she had accepted it, Cromwell’s report found the school had made no formal job offer, “in the strictly legal sense of those words.”

Cromwell said that Spiro, whom he refers to as “the Alumnus,” had spoken by telephone with an assistant vice president [at the University of Toronto] for a “pre-scheduled stewardship call,” which was initiated by the school. At the end of the hour-long conversation, Spiro had “indicated that as a judge he could not become involved,” but “wanted to alert” the school that Azarova’s appointment would be controversial and may cause reputational harm. “He wanted to ensure that the University did the necessary due diligence,” said Cromwell.…Spiro told Cromwell he had learned about the appointment from a staff member at the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs [CIJA], who had emailed him the day before the call. Spiro was a board member of the organization before he become a judge. The staff member asked Spiro to contact the dean, but Spiro refused, saying it would be inappropriate, said Cromwell.

The CIJA staff member had heard of the appointment from a professor at another university and Spiro provided Cromwell with the email and memorandum that person had sent. The email’s subject line read “U of T pending appointment of major anti-Israel activist to important law school position.” The email requested that someone find out the status of the appointment and continued: “The hope is that through quiet discussions, top university officials will realize that this appointment is academically unworthy, and that a public protest campaign will do major damage to the university, including in fundraising.”

Iacobucci knew about the phone call and the appointment’s potential for controversy, but Cromwell’s report indicates he was more concerned with immigration and employment law issues. His emails to the assistant dean and a member of the faculty advisory committee expressed his “considerable misgivings” about Azarova’s ability to get a Canadian work permit in time for her to be a practical choice and the fact she had requested summers off, which was unusual for a person in an administrative role. In Cromwell’s interview with Iacobucci, the dean said legal counsel had suggested an independent contractor agreement was the only way to make the timing work, but that the arrangement would likely have been illegal.

“My conclusion is that the inference of improper influence is not one that I would draw,” said Cromwell. He also said the nature of Spiro’s inquiry has been “misunderstood in much of the public discussion” as an “objection,” “complaint,” “attempt to block the appointment” and “external interference.”

“However, having the benefit of a detailed account from both parties to the initial conversation, my conclusion is that the Alumnus simply shared the view that the appointment would be controversial with the Jewish community and cause reputational harm to the University,” said Cromwell.

Anti-Zionists Object, Facts Be Damned

Despite the report’s clear conclusion that Judge Spiro had not contacted the school in order to influence (financially or otherwise) UT’s hiring process, Azarova’s advocates are doubling down on their pre-determined narrative.

ANTI-ISRAEL ACADEMICS ESCHEW EVIDENCE

For example, Queens University Law Professor Leslie Green—who was one of at least two law faculty at other universities to file complaints against Judge Spiro and UT Law with the Canadian Judicial Council (CJC) last September—insisted that the facts contained within Cromwell’s report indicate the very opposite of the Justice’s stated conclusions:

“This is a damning Report,” he says. “By the judge’s apparent admission to the Cromwell Inquiry… he was engaged in what has every appearance of lobbying to promote the interests of a pressure group. It is damning of the University of Toronto’s administration and culture, which shows itself open and receptive to such lobbying, and ready to act on it.”

“The bar and the public are now watching with grave concern how the CJC deals with the Spiro case,” says Green, who is professor of the philosophy of law and fellow of Balliol College, Oxford and holds a part-time appointment as professor of law and distinguished university fellow at Queen’s.

Another Canadian academic and author, one Alan Freeman—an “Honorary Senior Fellow at the University of Ottawa’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs“—wrote an article for online outlet iPolitics in which he claimed that Judge Spiro inappropriately issued a “not-so-subtle threat that fundraising would be harmed if Azarova’s appointment wasn’t cancelled…” Freeman continued, “If you thought the whole affair stank beforehand, reading the report won’t leave you reassured…” (Not a single person at the university who spoke with Judge Spiro has ever reported that such a “threat” was made, nor does the report mention any threat of the kind.)

For his part, Freeman has also argued (among other dubious contentions) that Canada should “NOT move its Embassy to Jerusalem” and that Donald Trump only did so during his time as U.S. President in order to appease his campaign donor, “pro-settlement advocate Sheldon Adelson”.

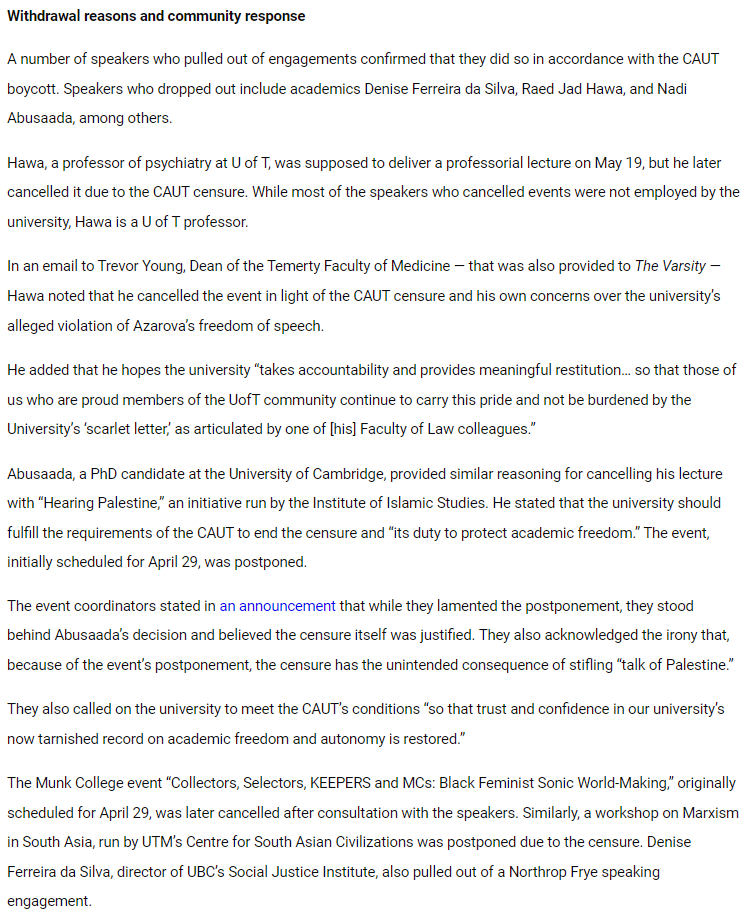

And in a bizarre twist, the Canadian Association of University Teachers Council (CAUT), which had—even before the release of Justice Cromwell’s report—objected to Dean Iacobucci’s decision not to hire Azarova, has now

taken the rare step of censuring University of Toronto for “serious violations of academic freedom” over a hiring scandal at the school’s prestigious Faculty of Law.

“The decision to censure was not taken lightly,” CAUT executive director David Robinson said Thursday in a news release from Ottawa. “It is a measure of last resort, used only when we are faced with serious violations of academic freedom and other principles that are fundamental to higher education.”

CAUT’s censure has reportedly prompted

several academic professionals [to pull] out of speaking engagements at the university, resulting in a slew of cancelled events across U of T in the past week. Speakers and event coordinators expressed concerns over a possible breach of academic freedom and the university’s response to the controversy and censure. They also emphasized the need for solidarity in the academic community and a substantive response from the university.

…In order for the censure to be lifted, U of T would have to take steps to “resolve the problem,” which CAUT representatives believe would include re-offering Azarova the position.

Naturally, BDS groups have shared news of these boycotts with glee.

“Chilling precedent.”

Academics are refusing to cross the picket line to speak at University of Toronto in response to @CAUT_ACPPU censure after @UofT rescinded a job offer over the academic's scholarly work on Israel's abuses of Palestinian rights.https://t.co/I9ga5QOy4X pic.twitter.com/K2ieso5chP

— PACBI (@PACBI) May 4, 2021

ACTIVIST-JOURNALISTS EMBRACE BIAS

Others, including Toronto Star journalist Shree Paradkhar, have attempted to justify their earlier leaps to conclusions by cherry-picking facts and excerpts from Justice Cromwell’s report. In one of her several subsequent articles on the subject, Paradkhar claimed that, according to the report,

We are to understand the only reasons the dean got involved in her candidacy, after being told that a major donor — a sitting judge no less — expressed reservations about it, were because red tape around work permits would not allow her to start on time.

But Paradkhar’s rendition is incorrect. For instance, on page 5 of the report, as in several places afterward, Justice Cromwell notes that it was always clear that, “the final “selection” of the person to be hired was to be made by the Dean.” The exhaustively detailed 78-page document also mentions several meetings (throughout the months-long hiring process) between the assistant dean, who was handling the bulk of the hiring logistics, and the dean—precisely so the dean could get “ca[ught] up” on the candidates and process. Moreover, the “red tape” Paradkhar so easily dismisses included warnings by German employment lawyers that the plan devised by UT Law’s Assistant Dean and UT’s employment lawyers to enable Azarova to sidestep Canadian work permit requirements in time for the start of the school year was “illegal and could potentially expose the university to liability.”

Still, in the same breath, Paradkhar urged the university to “make things right” by simply “giv[ing] Azarova the job now”; elsewhere, Paradkhar characterized Azarova’s extensive history of hyperbolic anti-Israel catastrophizing and work with terrorist-linked Arab NGOs as simply academic “critici[sm of] Israeli rights abuses in Palestinian territories.”

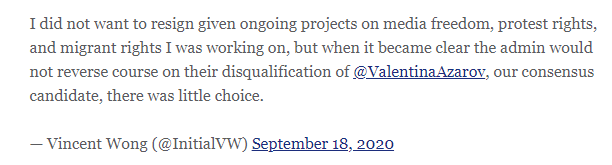

Yet another recent article on the controversy—this one in UT’s student newspaper The Varsity—featured the lamentations of Vincent Wong, a former IHRP staffer and one of a hiring advisory committee assigned by UT to evaluate IHRP candidates and make recommendations to the assistant dean and dean. He—along with the other hiring committee members—resigned in protest when Dean Iacobucci refused to change his mind.

[Screenshot of a now-deleted tweet by Vincent Wong, originally embedded in an article published in anti-Israel blog Electronic Intifada.]

When Evidence Proves You Wrong, Blame Collusion and “Elite Whiteness”

Wong has issued plenty of public comment on the situation, reinforcing others’ contentions that a shadowy injustice had occurred. In his lengthy op-ed on the case, published after the release of Cromwell’s report, Wong claimed that a (reportedly unpaid) single February 2021 keynote address by the Justice at the Center for Israel and Jewish Affairs’ (CIJA) annual legal conference, The Rule of Law in Times of Crisis, contributed to a “nakedly political [hiring] process”, given that Judge Spiro sat on CIJA’s board of directors before ever assuming his role in Canada’s Tax Court.

Furthermore, The Varsity reported,

In an email to The Varsity, Vincent Wong, a former IHRP research assistant who resigned due to the controversy, wrote that Cromwell’s report confused external influence as the primary factor with external influence as one of the factors of the dean’s decision to discontinue the candidacy.

“It is very reminiscent of a lot of human rights cases in which, for instance, sexism or racism cannot be pointed to as the primary factor motivating a decision… but all the contextual factors point to discriminatory treatment,” Wong explained.

He added that Cromwell seemed very willing to accept the dean’s denial of external influence despite the “contextual factors.” Wong wrote that the report is a prime example of how rhetoric could be used to come to any conclusion, and that many of the people who had decision-making powers in the university’s handling of the situation were white men.

“The consequences speak for themselves: Dr. Azarova has still lost her job, I as a person of colour have lost my job in order to faithfully bring details of this incident to light, Palestinian rights and international law with respect to the Israel/Palestine situation are now demonstrably a taboo subject in the law school, and the white men who are at the heart of this impropriety have thus far escaped any sort of accountability.”

Wong’s admiration for Azarova, and his rush to blame sexism and racism for his own choice to resign “as a person of colour” makes a little more sense when one considers his political leanings; he has a long history of reverence for identarian ideologies that are typically deeply hostile to Israel—including “intersectionality“. In an interview with an IHRP student, Wong once gushed about his experience at Columbia Law, where he “had the chance to work with some great critical race theorists, like Kimberlé Crenshaw and Kendall Thomas”. He has evidently contributed to Jacobin Magazine, a (Noam Chomsky-endorsed) “leading voice of the American left, offering socialist perspectives on politics, economics, and culture.” And his (now-deleted) Twitter cover photo paid homage to leftist, anti-Israel icons such as Angela Davis and Black Lives Matter‘s Patrisse Cullors.

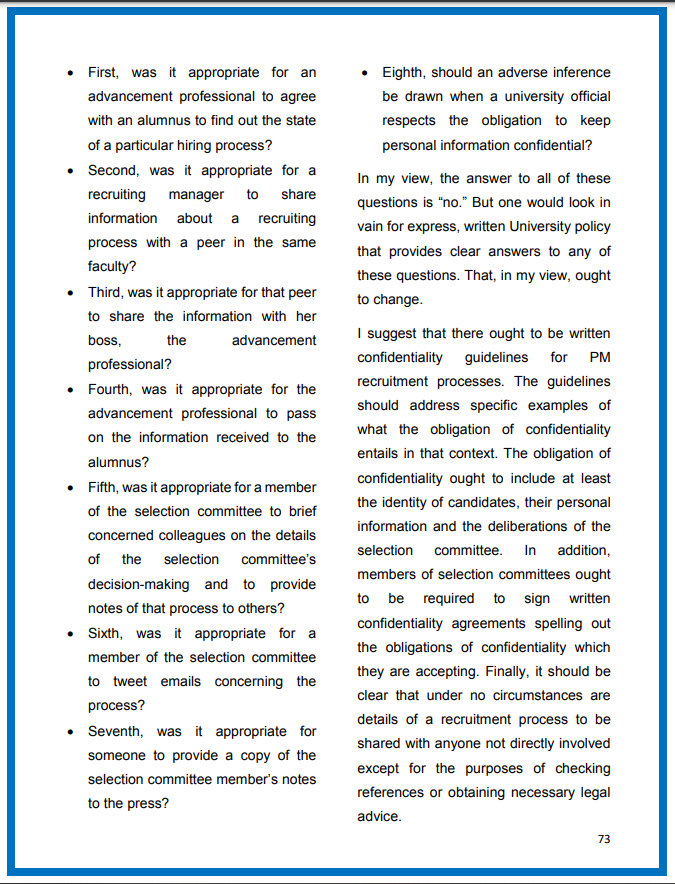

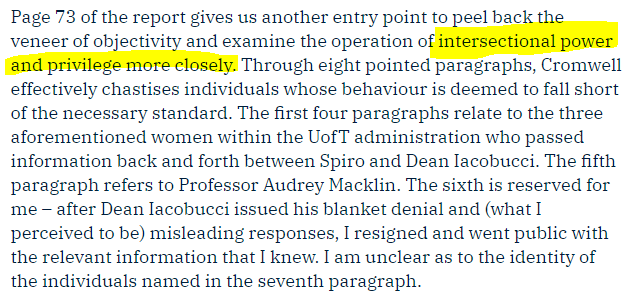

But Wong, like his compatriots, will not consider that they could themselves be guilty of the “grossly inappropriate meddling” of which they accuse Judge Spiro. Instead, he castigated Cromwell for a perfectly reasonable section of the report in which the Justice noted areas where UT’s hiring process did approach impropriety (the initial leak of hiring news to people outside university faculty, for example).

The fault Wong found in Justice Cromwell’s analysis? That it happened to be mostly female staff, and Wong himself, who were responsible for the problems Cromwell described. But, for Wong, Cromwell’s conclusions were simply the inevitable consequence of the “operation of intersectional power and privilege”. It was Cromwell’s and Spiro’s identities (at least, as Wong defined them) as “powerful white male[s]” that dictated the nature of the Justice’s assessment.

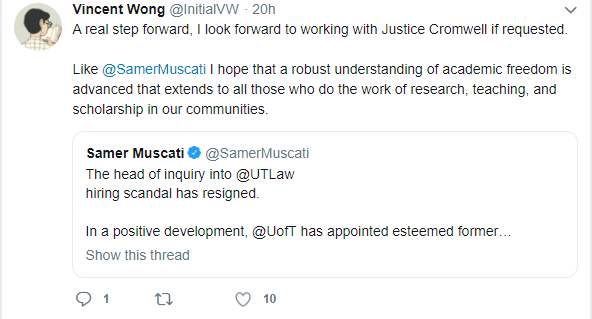

Nevermind, of course, that when UT selected Justice Cromwell to investigate the matter, Wong and fellow Azarova fan Samer Muscati both applauded Cromwell’s involvement—without regard to his status as “powerful white male”.

Conclusion: Zionist “Meddling”? Or anti-Zionist Political Warfare?

Ultimately, the Azarova affair (as perceptive readers might have gathered) isn’t really a case about academic autonomy or even of free speech. Instead, like so many others involving Israel on the college campus, it’s a case about bigotry, arrogance, and the propensity of intellectuals to self-delusion.

From the outset, Azarova’s champions have appeared all too willing to trumpet an explanation for her misfortune that would not feel out of place were it straight out of the pages of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Though they’ve clearly worked hard (as most BDS-ers often do) to dress up their charges in the ostensibly fair-minded language of pluralism and human rights, the hateful premise of their accusations remains obvious:

A powerful, wealthy Jew sneakily used money as leverage in his conspiratorial plot to engineer the world to his liking. Judge Spiro sought, of course, to prevent one of the noble, courageous few who speak truth to power from further revealing the sinister reality of his own people—those dastardly Israelis—and their oppressive behavior. Like so many weak-willed peons before him, Dean Iacobacci submitted to the lure of Jewish wealth and, when discovered, haphazardly tried to construct a cover-up. Luckily, wise defenders of morality from all over the world have risen to stand in solidarity with the brilliant Valentina Azarova—a faultless victim of

JewishZionist manipulation—and hold the corrupt accountable to the principles of freedom and justice.It’s a tired, familiar tale, but Azarova’s advocates have refused to consider any other possibility.

It can’t possibly be that, given their own political ideations, the unanimously pro-Azarova advisory selection committee members may have been predisposed in her favor, independent of UT’s selection criteria. It can’t possibly be that Judge Spiro merely inquired off-handedly without any intention of exerting pressure on the school (as Justice Cromwell found). It can’t possibly be that Azarova’s own repeated request “for summers off”—atypical for the post she sought—indicated to Dean Iacobucci that she didn’t quite understand what the job would entail (as Justice Cromwell noted). Nor can it possibly be that there was an accidental miscommunication that led Azarova to mistakenly assume she’d officially snagged the position—or that the timing of her work availability had always been a major factor. No, it must be that the rich Jew had tried to silence “talk of Palestine”.

For those activists, writers, and professors who jumped to this conclusion (however sanitized their versions appeared) before an investigation was conducted, Justice Cromwell’s report served as a threat to their credibility. Not only were they wrong, they had revealed their biased predilections. The solution to this problem harkens to a line from the groundbreaking 2013 book (Disinformation) by the late Soviet defector Lt. Gen. Ion Mihai Pacepa, in which he recounted one of many interactions with the architect of the Soviets’ vast political warfare apparatus:

As that very clever master of deception Yuri Andropov once told me, if a good piece of disinformation is repeated over and over, after a while it will take on a life of its own and will—all by itself—generate a horde of unwitting but passionate advocates.

Andropov’s was sensible advice, and Azarova’s army seems to be taking its cue from him by repeating the same falsehoods after the report’s release as before—regardless of the facts it spells out. The repetition is working, and hundreds of university faculty have energetically signed onto the myth. The confirmation bias is clearly strong with this crowd. Why?

In his essay “Scholarly Rights and Political Morality,” the noted economist Kenneth Boulding wrote, “The intellectual in power … is frequently a dangerous man, perhaps because his very capacity for analysis often gives him illusions of certainty in the situations that are objectively uncertain.” Just as Boulding described, and in the absence of evidence that supports their Jewish-money-and-power hypothesis, Azarova’s supporters have been forced—not only to double-down on their previous statements—but to interpret the facts in whatever way (however far-fetched or outlandish) will best facilitate the persistence of their discredited narrative.

Subjective, unfalsifiable (but oh-so-trendy!) allegations of “white male privilege” as the root cause of her failure ought to signal to Azarova’s supporters that they are grasping at straws; but anti-Israel zealots are not typically known for their dispassionate empiricism. And as we at LIF know well, Hell hath no fury like an anti-Zionist scorned.

———–

Samantha Mandeles is Senior Researcher and Outreach Director at the Legal Insurrection Foundation. You can contact her on Twitter at @SRMandeles.