Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.

— Robert Frost, “Mending Wall”

On Tuesday, the 10,000-member American Anthropological Association will announce the results of a vote on its proposed boycott of Israeli academic institutions. If the preliminary vote is any indication, the outcome is a foregone conclusion. It will pass overwhelmingly, condemning Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and targeting every institution of higher learning in the country.

That action, I believe, is misguided, counterproductive, and sure to damage both the association and the Palestinian cause. It also puts at risk any network of scholars by inviting similar future reprisals. Yes, I can see the emotional appeal of a boycott, but I am convinced by Israeli colleagues, students, and friends, as well as by my own experience in that country, that the boycott will harm the very people it is intended to help and embolden those whose hardline policies the AAA disdains. Beyond all this, the boycott itself is irreparably flawed and discredited by the historical and contemporary context that produced it.

For the record, I am Jewish, the grandson of a rabbi. I am American, and I am a professor. I readily acknowledge my bond with Israel. But I am no apologist for the Netanyahu government, the expanded Jewish settlements in the West Bank, the often unconscionable treatment of Palestinians, or the lack of proportionality in Israel’s response to attacks launched by individual Palestinians.

So why oppose the boycott? Let me go back for a moment. In the summer of 2015, with the support of a Fulbright, I taught at the University of Haifa, in Israel’s third-largest city and one of its most secular and progressive urban centers. The university boasts a student population that is one-third Arab. It is common to see student-soldiers of the Israeli Defense Forces, rifles slung over their shoulders, checking alongside their Arab classmates the same class announcement boards or discussing homework. Nor is it unusual for heated debates about Israeli policy to arise between Jews and Arabs in the classroom — and even more commonly, between Jews and Jews.

So how does a learned society like the AAA justify punishing the likes of the University of Haifa or see doing so as an effective message to the Israeli government? Many of my colleagues on the Haifa faculty openly criticize that government, as do their students. A wholesale boycott of academic institutions applies the same indiscriminate standard of punishment that the association says it abhors. The AAA would argue that you don’t bulldoze a house or bomb a block in Gaza because of one attacker. How then do you justify cutting off relations with all Israeli academic institutions based not on actions but on geography?To attack a nation’s universities, parastatal entities at most, for failing to be more aggressive in opposing their own government sets a dangerous if not ludicrous precedent. By that standard, every nation now sympathetic to Palestinian rights could justify a boycott of American universities for their failure to sufficiently oppose America’s military support of Israel. Imagine if all the perceived sins of the U.S. government, its foreign involvements and covert operations, were to be hung around the neck of American universities. (Would these same scholars champion a worldwide boycott of all American universities if Donald Trump were to become president and continue to suggest barring Muslims?)

More to the point, the Netanyahu government and its ever more right-leaning coalition could care less what happens to academics, given that so many scholars are overtly antagonistic to the administration’s policies. Indeed, there is every reason to think that Netanyahu will use the boycott to political advantage. This would not be the first time that the government has used external condemnation to concentrate power, vilify its critics for siding with outsiders, and cast itself as facing an existential threat all alone. The more isolated the government feels, the more it justifies its draconian policies, and the less it feels obliged to temper its responses.

What the association does not appreciate is that isolation as a weapon breeds only more isolation and gives greater license to those predisposed to crack down on both dissidents and Palestinians. Many members expressed outrage that Israel recently restricted the travel of the Palestinian astrophysicist and activist Omar Barghouti, one of the architects of the boycott strategy. But what did the association expect would happen after promoting a strategy that disenfranchises Israeli institutions? Did they think the Netanyahu government would not respond in kind? Remember Sun Tzu’s admonition: “Know thy enemy.”Does that justify the treatment of Barghouti? Of course not. But to be incensed by the response reflects a lack of understanding of the dynamics of regimes that sometimes turn to repression. It is precisely how South Africa reacted in the days of apartheid, and how China and Russia react today. Israel is a democracy — decidedly imperfect (although whether more so than America is an open question) — but a democracy nonetheless. Appeals to its democratic institutions, not a spurning of them, is the best hope for change.

Such a boycott also inadvertently tends to unite institutions and scholars from both the left and the right, feeling that they are under siege from abroad. Israelis are first and foremost Israelis. Anthropologists should understand better than most that herding together the like and unlike, supporters and detractors, only further cements a tribal identity. While some few may embrace the boycott, many more will resent the moral branding that is implicit in such an action. The AAA has conflated complicity with proximity, punishing an entire community for state actions over which many have little control.

In some ways, the boycott also reflects American academics’ own disregard for free speech. Such a boycott is the product of a culture that imagines it can promote free speech for some by squelching the free speech of others. Increasingly, those who argue for the rights of the disenfranchised here have tried to silence those of a different mind.

Some years ago, when I taught at Case Western, I invited a dozen Palestinian journalists to speak to my class and then to the university as a whole. They were articulate, thoughtful, and as unsparing in their criticism of the Palestinian government as they were toward Israel. But to my surprise, colleagues attacked me as a dupe of the Palestinian cause for giving them such a forum. Many boycotted the event in protest.

A boycott is the last thing the AAA should impose. What is needed is more interaction, not less. If there is any sector of Israeli society that holds promise as an agent of change, it is academe. (And perhaps the Israeli military, but that is a topic for another discussion.) Instead of boycotting these Israeli scholars, anthropologists should be hosting them, along with their Palestinian counterparts. Stigmatizing them with a boycott, without regard to their character or conduct, is the last thing I would expect of an organization representing the discipline of anthropology. It is reactive, not proactive; politically regressive — singling out not the powerful but the thoughtful — not progressive.

There is something unseemly, too, about the handling of this issue. On April 15, when voting on the boycott began, the group Anthropologists for the Boycott of Israeli Academic Institutions gleefully wrote, “The big day has finally arrived — voting on the proposed boycott … is now open!” The carnival atmosphere hardly seems befitting a learned body voting to turn its back on another nation’s universities. In Israel, such a vote stirs somber memories and deep internal conflicts. While the AAA accepts votes from members most of whom enjoy the comfort and security of their offices and research sites, members of the Haifa department where I taught continue to use a photocopier sharing space with a contraption designed to filter out poison gas in the event of an attack. (Scores of rockets have fallen on Haifa, which has also been subjected to suicide attacks on buses and restaurants.)

Proponents of the Israeli boycott often cite that imposed on South Africa beginning in the 1960s, but the analogy is anything but a clean fit. To the degree that earlier boycott can be credited with succeeding, it must be viewed in the broader context of integrated international sanctions that had sweeping economic, cultural, and political components. And very few black Africans got a higher education there even before the 1959 law that barred them from open universities. (In fact, some South African universities valiantly protested that law.) In Israel, there is no such ban on Israeli Arab and Palestinian students. While their numbers remains woefully low – averaging about 14 percent of the student population — there are myriad complex reasons for the disparity, nearly all of which are attributable to government policies, not university actions. The closest analogy would be Israeli treatment of Palestinian students from the occupied territories — including a deplorable security screen that they must pass and which is administered by the military, not by the universities.

Even so, the number of Arab students at Israeli institutions is on the rise — up from 9.8 percent in 2000. The proportion among candidates for master’s degrees rose from 3.6 percent to 10.5 percent during that same period. In the case of South Africa, a boycott could not have adversely affected black African students, because they were already excluded from university. The same may not be said of Israeli Arabs and Palestinians. Apparently because of a standing boycott by the American Studies Association, a Ph.D. student at Tel Aviv University was unable to find external readers for his thesis. The student is an Israeli Palestinian. Call him collateral damage.But even if one could argue that the boycott might be effective, and that its indiscriminate nature could be justified, it is still fatally flawed. Why? Because it is both utterly indiscriminate and wildly selective — which is to say, morally repugnant at its roots. From the world’s 196 nations, the AAA chooses Israel against which to concentrate its firepower, as if the human-rights violations and abuses of China, Cuba, Iran, Myanmar, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Syria were less disturbing to the association’s conscience. Given the back story of the Jews — and the AAA — one might be excused for raising the specter of anti-Semitism.

The American Anthropological Association, after all, has always been an organization with a selective conscience. It said and did nothing in 1935, when Germany passed the Nuremberg laws that mercilessly targeted Jews. It was not until December 1938 — three years after the passage of those laws, and a month after Kristallnacht — that it raised its voice opposing ethnic persecution, and even then the resolution did not mention Germany. And no, there was no boycott. At that same 1938 session. the AAA elevated to second vice president Earnest A. Hooton, a Harvard anthropologist whose work claimed that a physical study of the “Negro” documented the race’s propensity for violent crimes. He also advocated sterilization of the mentally ill, the diseased, and “criminal elements.”

During the McCarthy era, when many scholars, including fellows of the AAA, were victimized — their careers ruined, their loyalty questioned — the association, while opposing loyalty oaths, was otherwise notably silent. When the Soviet Union systematically subjected Jews to travel restrictions and persecution, the AAA was once more not to be found. Nor were there any threats of boycott directed at Chinese academic institutions after the massacre at the Tiananmen demonstrations of 1989 or as a result of the continuing repression of Tibet. On the other hand, in 2006, the AAA voted to boycott Coca-Cola products in solidarity with trade unions in Colombia. Talk about selectivity.

A boycott of Israeli institutions reflects neither moral courage nor strategic soundness, but is an act of groupthink, a fashionable response that will spawn self-congratulations but do nothing to address a festering human-rights issue. The real danger posed by a boycott is the damage it will do to the fragile international scholarly exchange of ideas, insights, and research. That marketplace draws its strength and credibility from the fact that it is inclusive, that all scholars, regardless of the policies of their home states, are welcome at the table. Any obstruction, any attempt to exclude institutions, compromises the integrity of the whole, just as if the United Nations were to allow only democratic states to be members. Even a single act of exclusion devalues and politicizes the whole, transforming it into yet another arena for political posturing and recrimination.

What makes international scholarly interaction so valuable is that it is defined by its ability to transcend politics, to afford all a chance to speak and to be heard. If it is allowed to be used as yet another political instrument, it will lose all credibility. The nature of such a network, its hallmark, is that it is open to the diverse, the divergent, and yes, even the disdained, that its representatives are not held answerable for the dictates of faraway capitals over which they have little say.

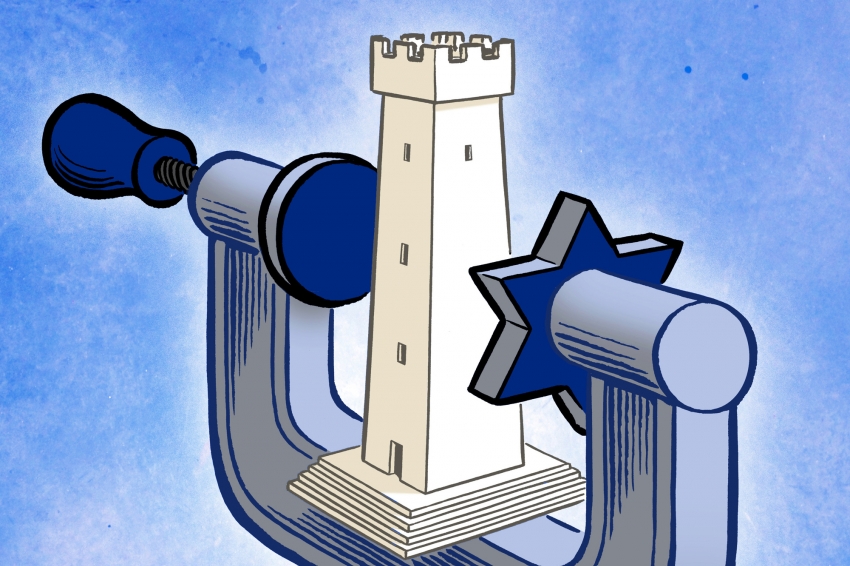

The AAA has violated that sacred covenant by launching a myopic assault not on those who disregard human rights but on the principles and promise of a network that might press for justice. Anthropologists lose all moral authority when they create more borders and more intellectual checkpoints. In so doing, they have inadvertently adopted the very strategies — containment and reprisal — of those they purport to condemn. Putting up a wall of any sort has never helped promote human rights.