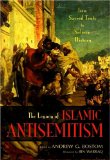

Here is a translation of a review by Shmuel Trigano of Andrew Bostom’s massive The Legacy of Islamic Antisemitism. The French original, “Vers une histoirede L’ANTISÉMITISME en Islam: un livre événement,” appeared in the November 9, 2008 issue of Controverses Sommaire. The translation is by Susan Emanuel.

Andrew G. Bostom, who has made himself known for the key book The Legacy of Jihad: Islamic Holy War and the Fate of Non Muslims, has now authored a monumental book that marks a turning point in the historical-philosophy of Antisemitism in Islamic lands: The Legacy of Islamic Antisemitism: from Sacred Texts to Solemn History. With the method already applied in his first book, these books generally mix a long study written by the editor with a considerable anthology of extracts from other authors, Muslim theologians, Orientalist scholars, and the historical testimony of travelers. The introductory overview by Bostom is very well constructed and gives the tone, but the extracts chosen from a multitude of authors that follow it are invaluable. They spare the reader an immense amount of research into texts written in a multiplicity of languages in the Middle East, and Western scholarship. Then can begin the real work on the subject in question for otherwise it would be necessary to read these hundreds of texts and studies in order to write a book than analyzes the substantive pith of the literature thus gathered.

I have deliberately employed the notion of “historical-philosophy” to characterize this editorial act. In effect, a strange (and understandable) phenomenon, both ideological and scientific has been produced in the domain of the history of Antisemitism in the lands of Islam: this history is quite simply eluded or ignored in the name of what an Israeli historian of Sephardic Judaism once defined to me as a “consensus among the community of historians:” the thesis of “Judeo-Arabic symbiosis.” Rare have been the historians who have ventured down this road that would have merited them (still today) the disapproval of their colleagues. Thus some great Orientalists have resolutely neglected or minimized, if not erased, this history, and have been followed by their disciples, creating a veritable false historical truth, attested to by academia, to the point that any contestation of this dominant story finds itself censured or stigmatized, taxed with being “unscientific”. Here I mention only the Israeli and American historians interested in Jewish history, but there are also straightforward Orientalists.

The ideological motivations of both are varied. Critiques of colonialism pretend that the colonized were innocent of any fault over an eternity – but that is not the only reason. The contempt of the history and memory of the Sephardic world has played its part, in a game of seesaw between Christian antisemitism and the Holocaust, stigmatizing one in order to exalt the other, by a pre-set contrast. Some of those involved were not blameless, in this constant seesaw between Zionism and colonial guilt. Thus the “neo-Sephardic” extreme Left in Israel has invented a marvelous Arab past in order to better strike out at Zionism.

This book precisely by its massive length and accumulation of documents and theses – a veritable encyclopedia – permits attributing “ideological motivations” to this historiographic current, which are even inscribed in academic forums. The thesis of Judeo-Arabic or Judeo-Islamic symbiosis simply does not resist this avalanche of proofs that contradict it. Here we have massive historical evidence that has rediscovered its contemporary character with the unfurling antisemitic wave that has been shaking the Arab-Islamic world for several years – which is in fact very well documented (but in French). Between these two periods, in effect, lies another history altogether: the colonial period was in fact for Jews the experience of a very great freedom and of astronomic social progress.

This is why I called historical philosophical the turning point this book represents. It modifies our whole perspective on the issue, even more than it re-writes the history, this historiography of what remains to be done and what it opens up. One will no longer be able to invoke scattered and forgotten authors to contest the dogma on the subject, but be able to refer people to this book. Then will begin the real work of writing the history of antisemitism in Islamic lands, which some historians have already bravely undertaken, as was, that of Christian antisemitism after the Second World War. Contrary to what the censors think, this history was far from destroying Judeo-Christian relations, but re-founded and strengthened them by airing that history. It must be said that the Christian world was not (and is not) in the drunken triumphalism that now embraces the contemporary Arabo-Islamic world. That critical vision of itself was acceptable, the occasion to reconsider Christianity’s relations with the Jews – which is what is to be hoped for in Judeo-Muslim relations.

Bostom does not assemble texts only from the Koran but also Hadiths, Sira, the law, theology, polemicists, and Orientalists, both pre- and post-modern. He adds numerous documents on the condition of the dhimmi and testimony from European travelers over the ages, with maps by Martin Gilbert that schematize the destiny of the Jews in contemporary Arab states. There are 766 double columned pages.

The central thesis of the book defends the obvious idea that the Islamic origin of antisemitism in Islamic land is a phenomenon sui generis and not imported from the West. Goitein, the great historian of the Geniza documentary record in Cairo, reports that the letters found there mention a new Hebrew word, coined to refer to the hatred for Jews: sin’uth; from sin’a = hatred; which is the most authentic word to refer to antisemitism in Hebrew, well before (i.e., in the early 12th century) Wilhelm Marr in the 19th century, inventor of the European vocable – just like the yellow star distinguishing Jews in their milieux was previously an Islamic invention…

The themes of this antisemitism sui generis are found in the Koran, which says that the Jews kill prophets and transgress against the divine will of Allah (Koran 2:61; 3:112), reject Mohammed (2:104; 4:46) and the Koran (4:155), falsify divine scripture (2:75), are the spreaders of war and corruption (5:64), and have been transformed into monkeys and pigs (5:60) – and this list is not exhaustive.

Nevertheless, in modern times forms of European antisemitism have penetrated the Arab world, notably during the Nazi era. In this respect, the trajectory of the Mufti of Jerusalem, head of the Arab revolt in Palestine and a dignitary to the Nazi regime, is exemplary of the many currents of Arab nationalism that chose the Axis against the Allies because the latter were colonial powers. Other recent books analyze this evolution. One can only note here how paltry the French literature has been. Undoubtedly, the “consensus” is still too powerful here – as shown recently by the disturbing “Guggenheim Affair.”