Although the essential facts of the Eichmann trial are known, the significance of this event is far greater and much more complex than would seem on first impression. In the simplest sense, the Eichmann trial was a trial of a war criminal brought to law by a state which did not exist at the time that he perpetrated his misdeeds. “Adolf Otto Eichmann (March 19, 1906 – May 31, 1962) was a German Nazi and SS–Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) and one of the major organizers of the Holocaust. Because of his organizational talents and ideological reliability, Eichmann was charged…with the task of facilitating and managing the logistics of mass deportation of Jews to ghettos and extermination camps in German-occupied Eastern Europe.”[i] As far as war criminals are concerned, Eichmann represented an innovation. He did not kill his victims personally, but was something new, a “desk murderer,” a Schreibtischtaeter. Although the Nuremburg Tribunal dealt with the problem of mass murder, the world was confronted with the challenge of comprehending how individuals of an outstanding cultural and educational level could form a devoted cadre of perpetrators.[ii]

Sixty years have elapsed since the Eichmann trial which took place in Jerusalem, Israel, during the Cold War, at a time when the experience of the Holocaust had been swept under the rug both in the West and in the East. For members of the North Atlantic Alliance it was convenient to forget the past. Old Nazis became new friends, and a rearmed West Germany was a pragmatic necessity. At the same time, it was policy in the communist Eastern Bloc to deny the fact that Jews preponderantly were the victims of the Nazi German Holocaust. In an act of negation, the dead were commemorated as “victims of fascism.”

In this cultural context, Ben-Gurion’s decision to bring Adolf Eichmann to law shocked the world. It forced the subject of the Holocaust and state-sponsored criminality onto the international agenda and influenced the writing and understanding of recent history both in Israel and abroad. For all its imperfections, the Eichmann trial had a profound educational value. For better or worse, the state prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, sought the testimony of the victims and gave them a voice. Like the Nuremburg Trials, it placed important testimony on the record. Was the Eichmann trial a show trial? Criminal trials do offer a stage for drama and showmanship, but anyone who has studied the real thing, such as those of Stalin in the 1930s, could never make this accusation in good faith.[iii] Fifty years later, the Eichmann trial is still remembered as an iconic historical event.

The Eichmann trial raised the issue of accountability, even of soldiers. Can an individual be absolved of responsibility for criminal deeds by resorting to the defense that he (or she) was only following orders? Furthermore, the trial took place in Israel, where the Mossad brought Eichmann by means of a kidnapping. In addition, there is the open question as to the extent of the responsibility of the Catholic Church, which enabled Eichmann to reach Argentina, and its role in actively assisting war criminals to escape justice, thereby becoming an accomplice after the fact.

One may also ask: if Israel did not conduct the trial, would there have been any trial at all? At the time of the Eichmann trial, in 1961, the field of genocide and Holocaust studies had not yet developed. Scholars still viewed the problem of state-sponsored mass murder mainly in terms of perpetrators and victims. Later on, for example, historians gave more thought to the responsibility of the bystanders, including the responsibility of the British Foreign Office and the American State Department, both of which had willfully obstructed escape and rescue of European Jews. We must still struggle to comprehend the disturbing implications of this problem in all its aspects.

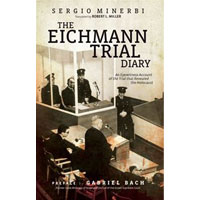

Sergio Yitzhak Minerbi is a retired Israel ambassador and a respected scholar who has written extensively on the attitude and policy of the Catholic Church toward the Jewish people. As a young man, at the beginning of his career, he covered the Eichmann trial for the Italian state radio and television (RAI). He produced a daily chronicle of the proceedings and ably described the atmosphere inside the courtroom and among ordinary Israeli citizens in Jerusalem. He shared his impressions of the duel between the prosecutor, Hausner, and the defense lawyer, Robert Servatius, the testimony of the witnesses, and the body language of Adolf Eichmann.

On the most basic level, The Eichmann Trial Diary has merit because it gives a day-by-day account of the ebb and flow of the trial, including its dramatic and boring moments. This helpful book may be less clever and pretentious than Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem but it is much more honest for the simple reason that Minerbi was present for the entire trial and Arendt was not. Minerbi’s account represents a welcome contribution to the historical record, and historians who will study this event will need to make use of it. At the same time, the text would have benefited from careful scholarly annotation, references to the current literature, and a more thorough retrospective analysis.

Nevertheless, there is a simple remedy. After reading The Eichmann Trial Diary, one need only pick up Deborah Lipstadt’s The Eichmann Trial, which provides the necessary background and perspective.[iv] Both books are short and readable. When read together, they complement each other very well.

DR. JOEL FISHMAN is a Fellow of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.

[ii] Michael Wildt, Generation des Unbedingten: Das Führungskorps des Reichssicherheitshauptamtes (Generation of the Unbound: The Leadership Corps of the Reich Security Main Office) (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition HIS, 2003). See Alexander Arndt’s review of this title in the JPSR: http://www.jcpa.org/JCPA/Templates/ShowPage.asp?DBID=1&TMID=111&LNGID=1&FID=388&PID=0&IID=1690.

[iii] See particularly Alexander Orlov, The Secret History of Stalin’s Crimes (London: Jarrolds, 1954).

[iv] See Deborah E. Lipstadt, The Eichmann Trial (New York: Schocken Books, 2011).