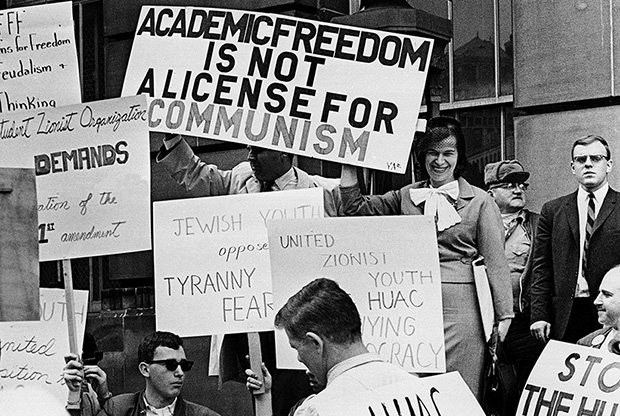

During the decade of Red-baiting, university boards and presidents were eager to demonstrate anti-Communist bona fides to their donors and to the public. Graduate students and professors were required to complete rigorous questionnaires. If compliance was unsatisfactory or refused, tenured professors were let go; untenured professors were fired or contracts were not renewed. In the event, the idea of academic freedom was submerged in an ugly reality of political and intellectual intolerance. I recall one of my father’s Jewish colleagues, who had been in the First Division of the Marines and seen heavy fighting on Guadalcanal. After the war, he was unemployable for several years because of his youthful radical politics and participation in front organizations.

It’s hard to imagine now a combat veteran being labeled a security risk or refused a job in public education or college teaching because of his or her political enthusiasms—precisely because of the standard of academic freedom. My father was appointed dean of the College of Education of the then-newly formed University of Hartford in 1957 and served for 25 years. In a survey of university administrators in 1963, there were still only 40 Jewish deans of secular universities in America, despite the growing ranks of Jews with doctorates. Today, that has changed: American academia is filled with Jews in senior positions.

Whether we are talking about the Young Communist League or Ban the Bomb then, or BDS now, the principle is, or at least should be, the same: A professor has the constitutional right as a citizen to engage in private political and social action outside the classroom and off campus without fear of repercussion by boards or administrators. But the recent open letters from university presidents framed in terms of academic freedom suggested a dark possibility: that a professor’s support of, compliance with or advocacy of an unpopular action or ideology that is inimical to stated institutional policy could have adverse professional consequences.

In one letter, for example, one president condemned the ASA resolution and cited the values of his college as set forth in its Long Term Strategic Plan. The juxtaposition of this condemnation with the college’s official strategic plan is a signal, consciously intended or not, that raises the possibility of administrative action—because in the long chain of AAUP statements, extramural activity by a professor contrary to the stated mission, goals, and values of his or her university may not be protected.

Academic freedom is meant to protect dissent, disagreement, and debate—and is essential to the discovery, interpretation, and transmission of knowledge. It is therefore worth protecting even if—and perhaps precisely because—it shelters provocative, and sometimes distasteful, opinions. On that point, I am sure my father’s generation, who entered academic life when it was often inhospitable territory for Jews and opened the doors for their children and grandchildren, would agree.